By Ryan Gentzler

Eagle Guest Writer

Earlier this year, Oklahoma Policy Institute released a report detailing the growth of fees attached to criminal court cases in Oklahoma. We found that as legislators attempt to prop up falling state revenues, fees have risen for every type of crime. When low-income defendants can’t keep up with payments on their enormous financial burdens to the court, a warrant may be issued for their arrest, leading to a cycle of incarceration that makes the climb out of poverty nearly impossible. Failure to pay court costs is among the most common reasons for bookings into the Tulsa County and Oklahoma County jails.

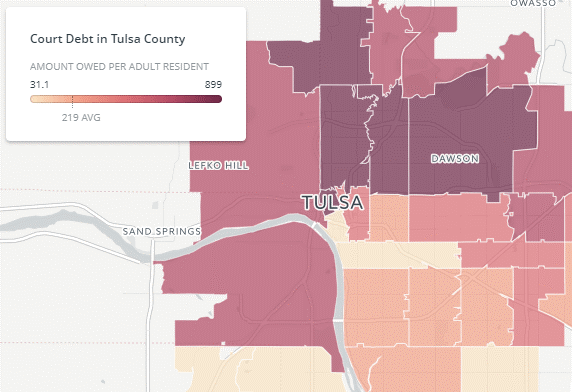

Though we’ve had a clear sense of the individual-level impact of this debt through the stories of those who are affected, it’s been hard to quantify the impact on communities as a whole. To get a clearer sense of the problem, we collected data on outstanding debts to the court from the state court system’s online ePayments tool for misdemeanor and felony cases filed from 2011 to 2016. The data, available only for 13 counties across the state, includes the age and address of the defendant, the number of charges on their case, and the amount of money they currently owe to the courts. It does not include other amounts that defendants may owe in relation to their case, such as supervision fees due to the Department of Corrections or the District Attorney’s office.

The data paints a striking picture of the people and communities that are hit hardest by the rise in court fees. In many areas of north Tulsa, for example, court debt amounts to over $300 per adult resident. It reaches as high as $590 per resident in Turley (ZIP code 74126), an area where about 57 percent of residents are black and 38 percent of residents live below the poverty line; in Turley, there is one case of outstanding debt for every five residents. The majority white parts of the county owe a fraction of that level of debt. The very high $899 in court debt per capita in the downtown Tulsa ZIP code is likely due to defendants who listed homeless shelters as their home address.

It’s a similar story in Oklahoma County: the highest debts per capita are found in south Oklahoma City ZIP codes with Hispanic/Latino majorities and in east Oklahoma City ZIP codes with black majorities. The highest debt ZIP code in Oklahoma County, however, had a per capita debt of about $260, less than half of its counterpart in Tulsa County.

There is reason to believe that the picture might remain the same for a long time. Many of the people who owe fines and fees to the courts may still be incarcerated and so are unlikely to pay off their debt quickly. Even defendants who are not incarcerated will struggle to pay off debts that are commonly in the thousands of dollars.

The data reveals why it’s so inefficient to fund our courts through fines and fees: it requires the courts to squeeze as much money as possible out of the communities that can least afford it. The criminal costs collected by the courts plateaued long ago; there’s little reason to expect we can collect more in the future. Instead, it’s time to look at ways to reduce debts for those who can’t afford them. Doing so could let our justice system devote less time to funding itself and more time to focusing on doing justice for victims and offenders.

Ryan Gentzler is a policy analyst with Oklahoma Policy Institute (www.okpolicy.org).